The Economist: Innovation beyond the comfort zone - White Paper By Équité | Dr. Daniel Langer

A report by The Economist Intelligence Unit

in cooperation with Équité

FOREWORD

We are fortunate to be able to call upon voices within the industry. In this article, we are pleased to introduce again Dr. Langer, an authority on luxury, lifestyle and consumer brands and regular speaker on strategic branding.

Are companies too comfortable? Is there a comfort zone, in which managers relax, day in and day out? Why do we suggest that there is a need to go beyond the comfort zone?

Although most managers are busy, stressed and have a large workload, we find that organisations can fall easily into a mode of complacency and comfort. The focus is far too often internal and imitation is often labelled as innovation. This creates a dangerous bubble, in which companies may feel secure, partly because the competition are doing the same. Whether via technological breakthroughs, changing consumer expectations, millennial disruption and digital, any market can change at any time. The speed of change has never been faster. Simply being busy is not enough anymore.

Getting out of one’s comfort zone is necessary in order to survive and lead the change. With a focus on true innovation, combined with precise brand strategies, companies cannot only master disruption but drive it in order to create sustainable competitive advantage.

We hope you enjoy the read.

Stefanie Siraghi

Director, EIU Consumer practice

Being comfortable is not an option

When Procter & Gamble (P&G) of the US bought Gillette in 2005 for US$57bn, the intention was to acquire a significant share of the growing men’s grooming segment, create offensive synergies and to accelerate the growth of the company. An article in Ad Age (February 15th 2010) cites the objective of the acquisition as follows: “Though P&G was already beating most of its competitors handily on the top line and in market share, chairman-CEO A.G. Lafley predicted that Gillette would add another full percentage point to the company’s annual sales growth. Gillette chairman-CEO Jim Kilts predicted [that] the integration of what he called the two best companies in consumer products would become the stuff of Harvard Business School case studies as P&G reaped the benefits of ‘reverse synergies’ from Gillette managers and practices and Gillette tapped P&G’s beauty-care expertise.” More than ten years after the acquisition, it is clear that none of this has materialised.

Even worse, Gillette, which for decades had dominated the men’s razor business, lost relevance and market share in a dramatic way. According to the Boston Globe ( June 21st 2017), Gillette’s market share plummeted from 70% of shavers and blades in the US in 2010 to 54% in 2016, representing a decline of 16 percentage points in a US$2.6bn market. The real market-share loss could to be much higher, as market research companies struggle to accurately estimate the digital sales of disruptors. From these numbers it is evident that there has been a substantial impact on revenue and profits. Some industry sources estimate a decline of up to 30% of Gillette’s revenue and around 80% of its profit over the past five years. Recently, Gillette announced that it would cut prices by approximately 20% in a desperate move to defend its market position. In all my years managing brands in highly competitive markets, I never saw a price reduction being able to reverse a fundamental brand issue. Mostly, the opposite happens: a weakened position deteriorates even further after reducing prices as profits continue to drop, both for the brand and for retailers.

This warrants the question: what happened? Why did Mr Lafley’s vision to add a full percentage point to P&G’s annual growth end in the catastrophic loss of market share, revenue and profit in Gillette’s core category, something almost unprecedented in the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) industry? How could the “two best companies” in the consumer space—according to Mr Kilts—allow this to happen?

One answer is comfort. With a market share of 70%, significant bargaining power with retailers

and a track-record of dealing with competitive challenges for more than a century, brand managers probably became too comfortable, too used to dominating the segment, and not sufficiently careful to anticipate external threats and adjust their business model early and radically enough. When market disruption happens, complacency is not an option. If it can happen to companies of the size and competency of P&G and Gillette, it can happen to any business.

Disruption around friction points

What happened to Gillette is what I call disruption around friction points. On the one hand, friction points offer enormous opportunities for brands that can find ways to address and solve them. On the other hand, they are significant threats to companies that do not manage them early and swiftly enough. Furthermore, they can be the end of companies and brands whose business model was causing friction points.

Friction points are parameters that make the life of consumers less comfortable, less convenient or less efficient. Addressing them provides an opportunity for business-model innovation.

In the case of people buying razors, there are at least two significant friction points:

l Whereas blades are cheap to produce, they are sold with significant mark-ups. When you buy

a cheap razor it includes one or two blades for free, but buying replacement blades becomes significantly more expensive. For decades consumers knew that they had to pay too much, but they had no real alternative or solution.Knowing that blades are expensive, many men do not change them often enough, resulting in poor shaving results and skin irritation over time.

As a result, consumers are convinced that they pay too much and are not always satisfied with the result. In addition, buying replacement blades means a trip to a pharmacy or grocery store, which is another friction point. Since this is so obvious, why was the razor business model not really challenged for more than a century? The answer lays in a symbiosis between the dominating brand, Gillette, and retailers around the world, who were content with a very popular brand on their shelves. Adding competitors or cheaper blades meant risking their shelf efficiency and profitability, which no retailer was really interested in doing. This model worked for decades until it evaporated in just a few years.

Digital connectivity opened the door for disruption and a solution to these friction points. A US- based company, the Dollar Shave Club, came with an entirely new business model, offering a digital subscription model that guarantees fresh blades at an affordable price without the hassle of going to the store to buy them.

Consumers began to realise that there was another option, and it was not just an alternative. By addressing major friction points, the Dollar Shave Club disrupted the entire business model of shaving and attracted millennial consumers to its brand. There suddenly existed an innovative and maverick brand. No longer was innovation around shaving just about adding a blade or two, or better-gliding strips, but rather a new way of buying and using razors. It was real innovation and disruption by solving friction points, instead of gradually enhancing the status quo, which had been the typical way

of innovating.

The real power of disruption is that the market leaders can hardly react if they are not those that solve friction points themselves. The Gillette model caused the frictions points; being “locked in” also means that it is difficult to compete when the rules change. Although Gillette now offers an online club model, too, the brand needs to balance online activity with trade activity and cannot adequately prioritise the new channel without alienating traditional retail partnerships.Brands that do not address friction points early enough risk becoming obsolete once someone else addresses them in a consequential and different way.

History repeats itself again and again. Kodak (US) underestimated digital photography for too long, convinced that consumers would always buy film because of its superior quality. What they failed to recognise was that the actual product they were selling was a memory. Digital offered more convenient options for capturing, storing, transporting and sharing memories. Nokia (Finland) dominated mobile phones worldwide but had no answer when Apple (US) launched a smartphone. It did not realise that communication was much more than voice. Blackberry, itself once a disruptor, also became obsolete when the only advantage it had, a keyboard, was merely one of many functions of a smartphone.

Similarly resistant to disruption, traditional car companies ignored electrification for too long and tried to convince consumers that the combustion engine was efficient and clean. Incumbents have tried everything to defend their old business model, including cheating on emissions. Instead of leading the change, the market leaders were reluctant to innovate, hoping that maintaining the status quo was an option. It never is.

Despite these risks of not innovating, the rate of innovation has slowed over the past three years. According to data from Mintel (see below), a market intelligence agency that tracks product launches around the world, new product launches (as opposed to relaunches or extensions) plateaued and even fell in 2017, compared to previous years. Whilst launches in food and personal care still dominant the market, growth in innovation is slowing in Europe and the US. However, not adapting could be a risky path.

Staying in the comfort zone for too long is not only dangerous, but it is also the recipe for becoming obsolete. Innovating beyond the comfort zone is the only way of leading the change over time.

The innovation rate trap and what does innovation mean, really?

Innovation is a term that is often used too casually, lacking precision. Merriam-Webster defines innovation as “the introduction of something new, a new idea, method or device.” In my opinion, this is blurry. Those aspects lack two critical factors: relevancy for consumers and the competitive landscape.

Just because an idea is new does not mean that there is any relevancy for consumers or that it is different enough versus competitive offers. Even if it is different and relevant, the idea needs to be exciting, touching the heads and hearts of consumers at the same time.. Only being new does not mean that something is an innovation.

In addition, the interpretation of what innovation is differs across the world. When I worked in Europe and presented a new product to a trade partner, say a new variant of a shampoo brand with new formula and technology, they would typically consider it as “innovation”. In North America and Japan, the same would not be seen as innovation but as “new flavour”. In my experience, Europeans see innovation as something technologically different (such as a new formula), North Americans as something structurally and visually different (such as a reworked packaging) and the Japanese as something that is futuristic.

Although these observations are generalisations, they underline that the term innovation may not be understood in the same way when used by different people or in different contexts. The same is true for the internal and external use of the word “innovation” by companies. Everyone wants to appear innovative, resulting in overuse of the term.

Companies tend to talk about innovation when they speak about a new product, technology, design or user interface within the realm of their own business. Hence, something may already be in the market for a long time, but when a company finally adapts the technology into their products or merely quickly follows the innovations of other companies, there is often a tendency to talk about innovation, while imitation may be the more precise description.

Companies regularly talk about innovation rates—often a percentage of sales by products introduced within the past two, three or four years. If every new product is described as an innovation, including imitations or minor design relaunches, companies communicate seemingly high innovation rates but, in reality, they have not innovated. Innovation rates are published to please capital markets and analysts, and sometimes even to motivate staff internally.

What may look great for public relations at first glance leads to a hazardous situation: the innovation-rate trap. A widely communicated but false innovation rate. When people hear something often enough, they may think that it is right even if it is not. Perception is reality. Once employees believe that their company is innovative, comfort and complacency settle in when a sense of urgency is needed. The innovation-rate trap is a dangerous deception and can lead to the destruction and irrelevance of brands.

Innovation makes the lives of consumers perceivably easier.

This leads to the question: what is innovation, really, and how to innovate beyond the comfort zone? We have already concluded that new is not necessarily innovative. At the top, many managers speak about incremental innovation, evolutionary innovation, revolutionary innovation and breakthrough, just to name a few. Many terms, little precision.

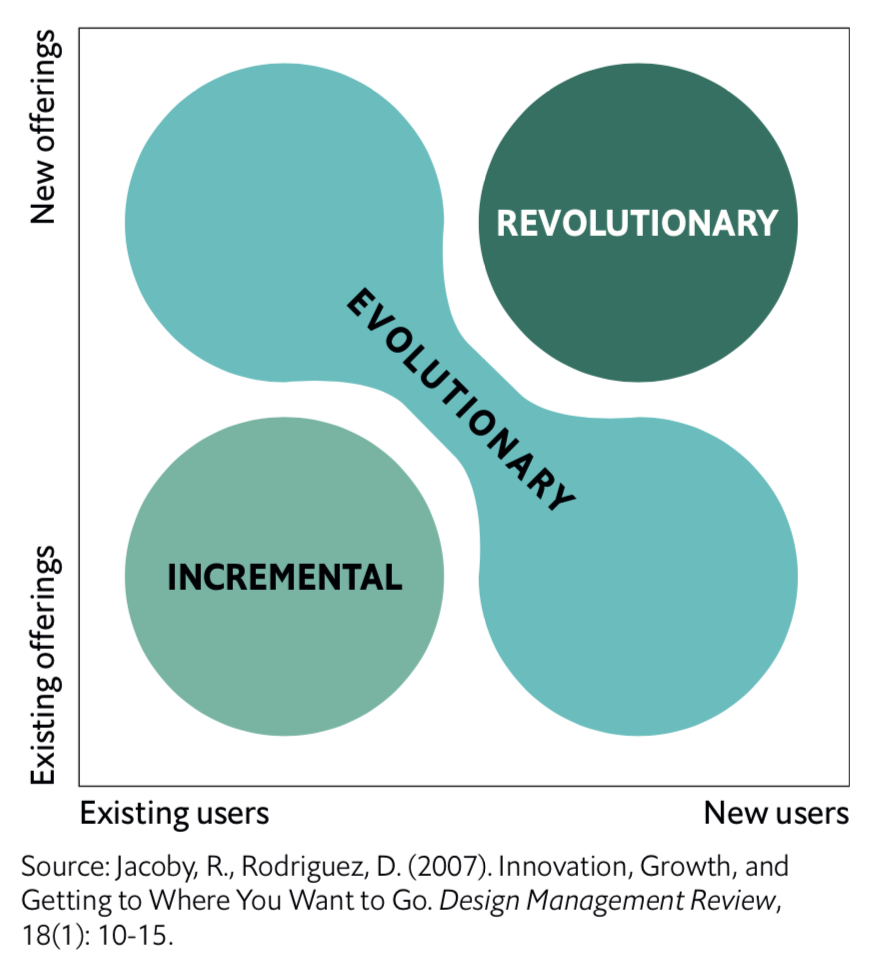

The “innovation matrix” by Ryan Jacoby and Diego Rodriguez is an attempt to cluster innovation using new and existing offerings and users as dimensions. Current offerings for existing users are incremental, and on the opposite end we find revolutionary items that are new offerings for new users. In between is what the matrix calls evolutionary.

Although we can argue that—in the extreme—a new offer for a new user may be “revolutionary”, there are definite limitations. What or who is a new user? If we look at ourselves as consumers, we are still the same person whether we buy a revolutionary product or not. And a new user could buy a new offering, but that does not mean that the new offering is revolutionary. It could just be a new product that that person had not bought before and similar to existing products.

The limitation of these kind of definitions becomes very clear. Most importantly, they are not actionable.

I propose a radically different approach to define and identify innovation. It has a straightforward criterion and is actionable:

Because innovation is all about solving a friction point, the result should be a more comfortable state in the perceptions of consumers. This is a difficult, binary criterion: if something new does not make the lives of consumers perceivably easier, it is not an innovation.

It may be something new, it may have utility or it may allow consumers to experience new technology, but there has to be a perceivable impact on the lives of consumers to be an innovation.

The iPhone was an innovation, because it offered so many different applications besides the phone: messaging, camera, photo album, door key, internet browser, email device, gaming console, remote control, fitness companion, music player and thousands more all in one device. In my view, this is

true innovation. Making the lives of consumers easier. And eliminating many world market leaders in different categories with just one product.

Because most new products fail, it is of utmost importance to be very selective and only pursue ideas that can make a significant impact on the market. Thus, I would go even further before speaking of an important and powerful innovation and ask four additional questions:

1. Is what makes life easier really relevant for many? If yes, then there is significant market potential.

2. Is what makes life easier really different from everything else that exists? If yes, then the offer is unique within the competitive space.

3. Is what makes life easier addressing an important insight? If yes, then the offer is important for consumers and will get interest.

4. Is what makes life easier really exciting? If yes, then there is the chance for an emotional connection and high involvement.

During all my years creating, developing and growing brands, I used the logic of this “Innovation Decision Tree” as one of the best predictors of success for a new product. As an example, the recently opened Amazon store in Seattle has a revolutionary payment system where consumers do not need to pay at a cashier. Instead, they sign in with their mobile phones when they enter the store, place products that they want to purchase into their bags and leave. There is no waiting time at check-out, taking products out of the cart, paying or packing, but merely making the process of shopping more comfortable and therefore providing innovation that is relevant, insightful, different and exciting.

The criterion of making life easier also applies to new business models and open innovation. In my opinion, it does not matter whether an idea is generated in-house, crowd-sourced, the result of open innovation, if it is a product or service or a new business model. The real point is that what we call innovation should make the lives of consumers easier, with relevant, new, different, insight-addressing and exciting offers. Innovation is really only about that.

Thus, although it may be enticing to sell the idea of imitation as innovation, the innovation-rate trap is a warning never to take the comfortable path. Imitations are not innovations and labelling them as such may cause additional comfort, until it is too late.

So, why do so many innovations fail?

There are various data points and statistics on how many innovations fail, but it is not easy to find the exact number. As failure is not as attractive as success, companies often withdraw products silently, redesign them and do not talk too much about anything that did not perform. However, it is safe to assume that 80-90% of new products fail. Failure is much more likely than success. Products that fail are either taken off the market or relaunched within the first three years. If a product relaunch does not fundamentally change anything, why should a flop become a success, suddenly? Comfort is not an option when it comes to reanimating a failed product.

Investments are typically significant for product launches; research-and-development (R&D) spending is in the range of several million dollars (or even billions) and advertising budgets usually in the double-digit or triple-digit millions. At an 80-90% failure rate, it becomes clear that companies need to manage innovation differently, leaving their comfort zone. The financial impact of reducing failure rates materialises in an immediate acceleration of revenue growth, helping to offset the costs of R&D and marketing. The impact on profit is drastic.

The main reason for failure in my experience is complacency. I am convinced that introducing a product with 99% execution quality instead of 100% will lead to failure in today’s crowded, hyper- competitive markets. With regard to developing a new idea, the default answer should be “no”, unless it satisfies all necessary conditions: the concept will make consumers’ lives easier, is relevant and exciting. And so on. In case of doubt, it is better not to launch and to go back to the drawing board.

I usually drive my teams crazy, send them back, again and again, until everyone is convinced that what we have at hand is fulfilling all criteria of the Innovation Decision Tree. This process needs discipline, a level of detail and scrutiny often stretching the comfort level of many. It also requires a rigorous evaluation and elimination process. It is better not to pursue 1,000 ideas that may be interesting at first glance, but that fail to get check marks on all criteria of the Innovation Decision Tree.

Consumer perception is key, not company perception. Even if only one brand has launched something similar before, the product should not be sold as innovation. It may be necessary to catch up, but it should not be labelled innovation when it is not. Being comfortable and complacent in a process where a mixture of strategy, creativity and rigorous selection are needed to achieve excellence in execution is where many innovations fail.

Do companies become more complacent?

It seems that there is a growing tendency to replace innovating with buying businesses and market positions. Looking at activity around the world, both the number of deals and the deal value show an increasing trend of mergers and acquisitions (M&A). Instead of innovating themselves, many companies are choosing to buy smaller, seemingly innovative enterprises. Others purchase large ones—as in the example of P&G and Gillette—hoping to acquire sustainable market penetration.

In addition, it has become fashionable for many companies to set aside venture-capital budgets to invest in start-ups in the hope of acquiring disruptive business models or at least learning from them. As we observe this paradigm shift from organic growth to “buying growth” across industries, this seems to confirm a certain level of comfort about innovation. Instead of building up rigorous processes that enable organisations to innovate more precisely, disruptively and successfully, many companies are shifting their focus to M&A.

There is a catch. If there is a lack of innovative thinking within a company, acquiring innovation will not solve the problem. Even worse, bureaucracy, processes and complex decision-making can kill an acquired innovation in no time.

In the context of M&A, the innovation-rate trap becomes even more apparent. Take, for example, a company selling a high “imitation rate” as an “innovation rate”, which also “buys” growth by acquiring companies (many multinationals operate this way). It creates a context where staff are busy integrating newly acquired assets and are convinced that they work in an innovative environment. Performance statistics will show growth though acquired business, deflecting from the real performance and even supporting the misconception of contributing through innovation. This is comfort at its best and likely a recipe for disaster. Everyone is happy even as the company may be underperforming and on the hunt for hungrier, more daring, more disruptive competitors– complacency and comfort, yet feeling safe and superior.

M&A does not guarantee long-term success, defence of the business model or sustained growth. Instead of complacency about the core business, innovation beyond the comfort zone is needed.

Why many “innovative” companies and brands don’t last

Is success only about innovation? Innovation is nothing without a winning brand strategy. Innovators who do not get the branding right will not be successful. They run the risk that what is new will be replaced by something more unique if they do not create a compelling brand story. Almost weekly I get a “suggested post” on Facebook about something new and fancy, maybe a new wearable, a new smart home device, a new gadget, a new app and so on. All seemingly innovative. One thing many of those posts have in common is that I practically never hear about the new fancy “breakthrough” product again.

It is not enough to be rigorous in the innovation process and forget the brand. Companies have to be as precise in their brand-building process, too. An innovation without the right branding is nothing, and this is what many innovative companies forget. Many companies confuse brands with trademarks. Just naming something and assuming that this means that it will become a strong brand is a similar mistake to confusing innovation with imitation. Brands require much more than just a trademark.A case in point is Jawbone. Hyped as one of the most innovative and most millennial-focused companies, Jawbone made a breakthrough with a Bluetooth headset that seemingly outperformed existing products in the market and looked attractive. It also launched Bluetooth speakers and the Jawbone UP, which for many was the best wearable fitness tracker with a motivating, easy to use, well-programmed app working across multiple platforms. As a result, Jawbone received one of the highest venture-capital funding deals ever given to a technology start-up. Still, it went into liquidation when competitors outperformed all its technologies.

Jawbone had two issues: it went from innovation to complacency, losing its edge technologically. It also failed to build a brand beyond a trademark. This may sound surprising given that Jawbone had significant brand awareness. But what was Jawbone as a brand? What did the brand stand for? What was the brand equity aspiration? What did the company want to inspire in consumers? What was the “why” when it came to Jawbone, or even the “what”? What was the unifying brand element between headsets, loudspeakers and fitness trackers? What was the purpose of the brand? If people buy trademarks instead of brands, success will be short-lived.

In our observation, many innovative brands fail to do proper branding and to develop holistic brand strategies. Without branding, technology and innovation are worth nothing. If the technology gets traction, someone will imitate it. Technology will not survive if there is imitation and brand equity

is missing.

Innovation and branding go hand in hand. Technology will be copied faster than managers think. What seemed a point of difference at the time of development will quickly be eroded away if the brand proposition is not distinctive enough. This is a paradigm shift in innovation management. There is no lasting innovation without a systematic branding exercise.

This is not only a challenge for high-tech companies; it affects every industry. Moving from Silicon Valley to hospitality, in recent years there has been a shift in customer expectation from booking merely a hotel room to booking an experience. Brands such as W were first-movers in creating spaces where locals and guests could mingle and mix—a different experience than those provided by traditional hotels.

Now many hotel brands adopt the concept but fail to create a unique and distinct “brand experience”. However, if the experience is not distinct and not part of a differentiated brand strategy, then it becomes just a feature rather than something “ownable”. If it is not ownable then it will not last.

Innovating beyond the comfort zone

By now it should be clear that innovation cannot be mistaken for imitation and that innovation without brand strategy will not lead to a sustainable competitive advantage. The implication for managers is to think radically different, as well as holistically, when it comes to brand strategy and innovation.

The best companies first try to audit and rigorously define their brand in every detail. Not once, but at least every two years, and in today’s fast-paced markets even yearly. A sharp brand definition is a must. Although different brand-equity development tools exist, many lack the depth to build a really powerful, competitive, differentiated, relevant and lasting brand position. Hence, for brand audits and brand-building processes at my own brand development firm, we use our own proprietary methodology. In almost every brand audit we found significant improvement potential, with immediate impact on revenue growth acceleration and profit growth opportunities.

We also use Brand Equity modelling when we develop the branding strategy to bring innovation to life. Its power lies in an ultra-systematic, non-compromising process starting with a major brand diagnostic. In the process we analyse all parameters ranging from market dynamics, consumers, competition, intended positioning, rational branding elements to emotional components. Ultimately, we dissect what are points of parity (no difference) and what should be points of difference. Points of difference are then assessed for relevance. Once the exercise is concluded, the ultimate purpose of the brand is defined in a structured manner.

In many cases, the systematic brand-building process leads to the development of significantly more successful business models, pricing opportunities, and innovative products and services. Because it is all about relevance and differentiation, it forces holistic and disruptive thinking.The model helps to avoid just creating a trademark instead of a brand. Brands need a unique proposition, beyond technology. There should be a playbook about all aspects associated with the brand, including how consumers should resonate with it.

What many companies do not do is optimise the customer journey: where nothing is random and every consumer touch point strengthens brand equity. Few companies get the customer journey right. A rigorously managed journey strategy can be a game changer for growth, loyalty and brand power. If brand model and customer journey are not well executed, the brand will remain blurry, not differentiated. This makes it challenging to generate sustained competitive advantage or convince consumers to pay a premium.

As branding and innovation go hand in hand, innovation needs to be planned as systematically as the brand strategy. Top management needs to be fully involved and accountable for innovation. Companies which believe that innovation can be delegated to departments without very close governance and oversight underestimate the organisational challenge to transfer an innovation from idea to product successfully.

Too many compromises and lack of attention to every detail contribute to weak execution, resulting in poor market performance. And in many companies, too many people have a say in the final product. But when it comes to innovation an overly democratic process, where every internal stakeholder is pleased, leads to mediocrity. Therefore, innovation should ultimately be the responsibility of the CEO. It should be developed in teams but challenged, endorsed and owned by the CEO.

There cannot be any excuse for weak execution, and weak means anything less than 100%. The attitude of ultimate commitment to excellence and perfection will be embraced by everyone only if it is lived by example from the top. To achieve this, a systematic innovation process is needed with goals, KPIs, governance, performance-based reward systems, controls, milestones and check-in points. Innovation does not happen in an uncontrolled environment, but rather where creativity is paired with goals, deadlines, leadership, decision-power and structure.

What you do not find among the most innovative companies is comfort, because real innovation needs to go beyond the comfort zone. This entails combining a relevant, different, insightful and exciting idea that makes the lives of consumers easier with excellent brand strategies and optimised customer journey. It takes an incredible amount of processes, creativity, discipline, dedication and self-criticism to achieve the perfection needed to innovate in today’s crowded space.

Conclusion – Leaving the comfort zone is a must

Comfort is not an option if organisations want to be comfortable with their innovation results. Comfort is not an option when brands want to outperform strong peers. Comfort is not an option if teams want to survive. Innovation is never imitation. The ultimate decision-making bodies are consumers voting with their wallets. As a consequence, we should treat new ideas as innovation only if they resonate with consumers and if they are genuinely new in their eyes, make their lives easier in a relevant, insightful, exciting and different way. All of this should take place in the eyes of the consumer, not just by internal standards. Innovation is the responsibility of top management, and the responsibility cannot be delegated. It is not enough to demand that teams come up with innovative products. A demanding innovation culture has to be embedded in the organisation from top management throughout all levels.

The fundamental questions are: does what we do really make the lives of consumers easier? Is it really different? Is it really new? Is it really relevant for many? Is it exciting enough? If just one of these questions cannot be answered with a clear yes then failure is predictable. If there is one no, even a maybe, it is better to rework an idea again and again until a maybe becomes a yes. And if after ten, 20 or even 100 revisions it is still not a yes, then it is a no. Innovation has to fit and strengthen the brand. The brand cannot be the afterthought but needs to be the central consideration. What works for brand A probably does not work for brand B.

Breakthrough technology is where many branding mistakes are made. Being so busy with bringing seemingly disruptive technology to life, companies do not pay enough attention to the brand under which they will sell the technology. They forget that the brand is everything, that a very well-defined brand will outlast the technology and that the technology itself will be obsolete the moment a better solution comes to the market.

Many established players do the same—confuse a trademark with a brand, and by this not realise the real growth potential. Innovation beyond the comfort zone: it requires new thinking—much more holistic, bold, differentiated and consumer-centric, always keeping the point of difference to competition in mind. One is required to say no when the offer is not yet good enough. The time for compromise is over. If your teams are in the comfort zone, the result will not be innovation. Your company may not be around much longer, all because someone else innovated beyond the comfort zone.

About the author

Daniel Langer is founder and CEO of Équité, a leading global luxury, lifestyle and consumer brand development firm that elevates brands to increase their revenue, profitability and brand valuation. Daniel is an authority on premium, luxury and beauty brands and serves clients in many sectors, also including automotive, fashion, luxury, accessories, hospitality and services (B2B, B2C). He holds a PhD in luxury marketing, and is author of several top-rated books on luxury management in English and Chinese. He held top management positions in the beauty industry in the US, Japan and Europe, where he developed several triple-digit million-dollar brands from scratch and managed billon-dollar businesses. He lives in the US, works all around the world, speaks seven languages and enjoys yoga. For more information visit equitebrands.com.

Équité partners with EIU Consumer on strategic branding projects.

About EIU Consumer

The Economist Intelligence Unit’s consumer practice – EIU Consumer – provides industry award-winning, data-driven business analytics and strategy solutions, working with senior management of the world’s most dynamic consumer-facing companies. From macro to micro we connect our forward-looking view of the world to what it means for your business today and tomorrow by category, product or channel. Part of The Economist Group, we share the principles of independence and intellectual rigour leveraging our unique network of 900+ analysts and contributors globally, to provide you with independent evidence-based insights through applied intelligence.

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2018